Weight Expectations: Visualizing the Average Man and Woman's Bodies

Weight Expectations: Visualizing what the average person looks like, wishes they looked like, and wishes their partner looked like

- Women with “perfect” bodies have roughly the same level of body confidence as a typical, overweight man.

- 91% of women and 67% of men with average-looking bodies want to lose weight.

- People with “apple” and “pear” shaped bodies have the lowest confidence and are rated less attractive by their partners.

- The typical woman wants to lose 48 lbs, but her partner thinks she should lose around half that.

- 39% of people in going steady relationships want their partner to lose weight, rising to around 60% among married couples.

- Men and women both overestimate how slim and/or muscular their partners would ideally like them to be.

To find out how the average man and woman feels about these competing social forces, we asked 1,000 Americans to use a 12-point visual scale to reveal the body sizes and shapes that best represent them and their romantic partners. The combined results show what people look like compared to what they wish they and their partners looked like.

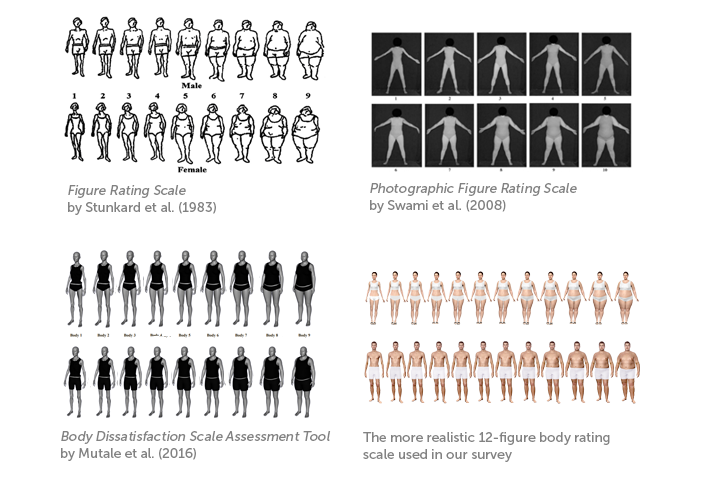

A brief history of body rating scales

One way to build a profile of a person’s body is to combine multiple measurements, such as his or her height, weight, and body fat percentage. While this is an accurate method, it can be hard to know how people feel about what those numbers represent.

…when you think about what you’d love to look like naked, you’re more likely to picture a celebrity or model whose body you consider perfect than recall stats from a chart.

After all, when you spot an attractive person in the street, or catch an unflattering reflection of yourself in a store window, your gut reaction (or reaction to your gut) is completely based on visuals, not abstract numbers. Likewise, when you think about what you’d love to look like naked, you’re more likely to picture a celebrity or model whose body you consider perfect than recall stats from a chart.

Researchers got around this problem with the introduction of the Stunkard Scale in 1983.4 This rating scale showed nine hand-drawn male and female figures, from which research subjects could choose the drawing that best represented their actual and ideal body size, ranging from extremely thin to extremely obese. Although this scale has been used in influential studies on topics ranging from body satisfaction to eating disorders, it has its limitations. One flaw is that the black-and-white line drawings are crude and unrealistic.5 They’re also rather simplistic, failing to consider body shape as well as size.

…we combined the best elements of previous figure rating scales into two new 12-point visual scales, one for men and one for women. Each showed the same photorealistic man or woman, ranging from very slim to very large.

25 years later, in 2008, researchers decided to test whether an improved visual scale, namely the Photographic Figure Rating Scale (PFRS), could be used by test subjects to accurately gauge BMIs. The results showed that the more realistic 10-point scale worked.6 However, it still wasn’t perfect: faces were obscured, which could prove off-putting, and because the images were based on various people, leg length differed between figures, which could potentially distort perception. In 2016, yet another scale was developed, this time using computer-generated figures, which allowed improved consistency between images.5

For our survey, we combined the best elements of previous figure rating scales into two new 12-point visual scales, one male and one female. Each showed the same photorealistic man or woman, ranging from very slim to very large. We made sure figures were totally consistent and highly realistic. To increase accuracy, we also provided respondents with multiple body shapes to choose between (e.g., “hourglass,” “pear,” “apple”), and 12 degrees of muscularity.

There’s an estimated 48 lb weight difference between the average woman’s body and the body she’d ideally like to have. This is based on the combined answers of the roughly 500 women who chose their actual and ideal body size from our visual scale.

By converting the body images used in our rating scale back to body measurements, we see that, based on an average height of 5’4”, the average woman weighs 172 lb and has a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 29.5, which puts her right on the edge of obese, according to World Health Organization guidelines.7 In contrast, her ideal body is significantly slimmer, at 124 lb and a BMI of 21.3, which is squarely within the “normal” range.

Women who were the ideal weight according to the average man still wanted to lose weight in 65 percent of cases.

Coincidentally, the average ideal female body weight of 124 lb is identical to Kim Kardashian’s weight when she married Kanye West in 2014, although our female respondents couldn’t have known this when they gave their answers.An overwhelming 91 percent of the women with the average body size said they’d like to lose at least a little weight, while 65 percent of women who were already at the ideal size said the same. This result has been echoed in other countries. In 2015, an Australian poll showed that 90 percent of overweight women wanted to lose weight, while half of women who weren’t at all overweight wanted to lose weight too.

The average woman rated her body confidence 6.1 out of 10.

A woman with the ideal body according to other women rated her body confidence at 6.9 – just 0.8 higher.

What about from the women’s point of view? At the average size, women gave an average body confidence score of 6.1 on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being most confident. At the ideal and much lighter size, the average was 6.9 – an increase of just 0.8. This seems like quite a small leap for such a large drop in weight. Is it the same story for men?

Based on 500 men’s selections from our male body size, shape and muscularity scales, a man of average height (5’9″) weighs an average of 197 lb with a BMI of 29.1 – technically “pre-obese,” but more colloquially described as having a “dad bod.”

67 percent of men at this size want to lose some weight (about the same as the percentage of women at the female “ideal” size). Men with this typical body appearance had an average body confidence score of 6.8 – almost identical to the female ideal. This is despite only 12 percent of women thinking the actual male body is visually perfect (compared to 9 percent of men about the actual female body).

On average, men rated their body confidence 6.8 out of 10.

Men with the ideal physique according to most other men rated their confidence at 8.2.

If men had the choice, they’d drop 11 pounds and swap much of the fat for muscle. The ideal body appearance according to them is considerably more toned than the actual, and men who already look like this report a confidence score of 8.2 – 1.4 points higher than men who look average. Nevertheless, 35 percent of men who apparently already look ideal would like to lose some weight, which is nearly half of the equivalent female group.There’s less consensus among women on what the best body for men looks like, as just under 1 in 5 women agreed on the muscular physique you see above, compared to just over 1 in 3 men for the slim female ideal.

So, on average women want to lose a lot of weight; men want to lose weight and gain muscle; and – based on people already at the “ideal” size – men would enjoy a bigger boost in confidence if they could achieve their idea of perfection. For an overview of what’s going on here, we can plot our respondents’ average body confidence against their BMIs.

On average, men reported having higher body confidence than women. 78 percent of men gave a score of 5+ out of 10, compared to 57 percent of women. One in five women said they had high body confidence (8+), versus just over one in three men.

Among both genders, only a small fraction said they have complete body confidence (10 out of 10): 3 percent of women and 5 percent of men. On the other hand, over twice as many women (7 percent) said they had zero body confidence, compared to a tiny 0.4 percent of men.

Both genders’ body confidence dropped as their BMIs (i.e., weight) increased. A man with a BMI of 22 (middle of the “normal” range”) on average had a body confidence score of 7.6, compared to 6.4 for a woman with the same BMI. At a BMI of 30 (around 50 lb heavier), men’s confidence dropped to 5.1 and women to 4.3.

Everyone carries their weight differently; some are curvy all over, while others are top- or bottom-heavy. We asked our survey takers to tell us which body shape best matched their own, then calculated the average body confidence score for each group.

Among women, the most confident were those with “rectangle” body shapes (6.4 out of 10), which means they carry weight proportionally, with their hips and bottom in line with their top half. In close second were women with the classic “hourglass” shape (6.2), which means a fuller bust, smaller waist, and a rounder bottom and hips. In evolutionary psychological theory, the hourglass figure is said to visually communicate to potential mates that a woman is fertile and has high reproductive potential, hence its enduring allure across generations and cultures.10

The least confident female body shape groups were “apple” and “pear” (4.3 and 5.1 respectively). “Apple” bodies are generally round, fuller around the middle, with a less defined waist. “Pear” bodies are bottom-heavy, with fuller hips and thighs. Both shapes go against the attractive “hourglass” theory, which could explain the lower confidence of women in these groups. Beyond aesthetics, people with apple-shaped bodies face an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and high cholesterol.11 Whether or not they knew this, 85 percent of women said they’d rather have an hourglass figure than be apple-shaped.

The least confident female body shape groups were “apple” and “pear” (4.3 and 5.1 respectively). “Apple” bodies are generally round, fuller around the middle, with a less defined waist. “Pear” bodies are bottom-heavy, with fuller hips and thighs. Both shapes go against the attractive “hourglass” theory, which could explain the lower confidence of women in these groups. Beyond aesthetics, people with apple-shaped bodies face an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and high cholesterol.11 Whether or not they knew this, 85 percent of women said they’d rather have an hourglass figure than be apple-shaped.

Women rated male partners with the “inverted triangle” body shape 8.2 out of 10, but the “apple” 7.3.

Men rated female partners with “hourglass” figures 8.8, but 7.4 for the “apple.”

Like women, men with pear- and apple-shaped bodies were the least confident (6 and 5 out of 10 respectively). The most confident men had the “inverted triangle” shape (8.2 out of 10), which in evolutionary theory is the equivalent of the enviable female hourglass.12 This shape, characterized by a dominant muscular upper body, with broad shoulders and narrow hips, is said to indicate higher testosterone and good health.

People’s confidence in their body shapes appears to correlate with how their shapes are perceived by their partners. We asked people to select their partner’s body shape and rate how attracted they are to their body out of 10. Women rated male partners with the “inverted triangle” 8.2 out of 10, but the “apple” 7.3. Men rated female partners with “hourglass” figures 8.8, but 7.4 for the “apple.” Although it’s difficult to directly compare the confidence and attraction scores, it’s interesting to note that women with “apple” bodies have an average confidence score of 4.3 but their partners rate them 7.4 out of 10 in attractiveness. The same applies to apple-shaped men: 5.3 in confidence, 7.3 in the eyes of their partners. It seems we’re our own worst critics, as none of the shapes for either genders scored lower than a 7 in the opinion of their partners. So, if we generally feel positive about how our partners currently look, does that mean we wouldn’t prefer if they were a different shape or size?

When women selected the body they’d most like to have, the average was a slim figure weighing 124 lb. Only eight percent of women we surveyed already matched this appearance. When men used the same parameters to build the female body they’d most like their partners to have, the average weighed 20 lb more: 144 lb. More than twice as many women (20 percent) had this appearance than the slimmer version the women collectively chose. It therefore looks like a lot of women overestimate how slim their partners wish they were, or they’d like to be slimmer regardless of the majority male preference.

When the men selected their ideal body, the average weighed 186 lb and was pretty muscle-bound. Seven percent of men said they currently looked like this. Women’s average ideal male figure was muscly, but 12 lb lighter – ripped, but a bit less jacked than what men preferred. Still, only 1 in 10 men said they looked like this, which makes the body that women most want their male partners’ to have twice as uncommon as the men’s ideal female body.

An almost identical proportion of men and women (50 percent and 52 percent respectively) said they’d like their partner to lose some weight. Both genders had even higher expectations of themselves, with 60 percent of men and 87 percent of women wishing they were lighter. On average, a woman of average height and weight indicated she’d like to lose 48 lb, whereas her partner said 28 lb would be more appropriate. Men were typically less extreme, wanting to lose 11 lb, while their partners indicated they’d prefer for them to lose 23 lb. However, based on their previous body scale selections, much of that would mean switching fat for muscle.

…a woman of average height and weight indicated she’d like to lose 48 lb. Her partner said 28 lb would be more appropriate.

Looking at specific relationship types, about the same proportion of men and women in going steady relationships said their current weight was ideal (24 percent and 21 percent respectively). However, among married couples, the figures were 23 percent for men (practically no change) but only 4 percent for women. Put another way, 93 percent of married women wanted to lose weight, compared to 74 percent of women in going steady relationships.

Men and women who are going steady have identical expectations for each other: 39 percent would like their partner to lose some weight. Among married couples, the number rises but the proportion stays almost the same: 60 percent of women and 57 percent of men. The sexes don’t get pickier as time goes on for no reason. Previous research has shown that between early adulthood and the age of 55, the average American man and woman gain 19 pounds and 22 pounds respectively.13 However, that doesn’t mean everyone should rush to the treadmill. Among our survey takers, 1 in 5 men who were already the ideal weight according to women still wanted to lose weight. Among women, it was 7 in 10.

Men and women who are going steady have identical expectations for each other: 39 percent would like their partner to lose some weight. Among married couples, the number rises but the proportion stays almost the same: 60 percent of women and 57 percent of men. The sexes don’t get pickier as time goes on for no reason. Previous research has shown that between early adulthood and the age of 55, the average American man and woman gain 19 pounds and 22 pounds respectively.13 However, that doesn’t mean everyone should rush to the treadmill. Among our survey takers, 1 in 5 men who were already the ideal weight according to women still wanted to lose weight. Among women, it was 7 in 10.

Men and women tend to find partners with similar BMIs to them most attractive – in relationships, at least. As a person’s own BMI goes up, so too does the BMI of the body they’d most like their partner to have. Far from opposites attracting, people tend to prefer partners who are similar to them. This is called “assortative mating” and it expresses itself in many ways, including personality, education, height and – as we’ve seen here – weight.14

It might be just as well that people prefer partners with similar bodies to theirs, as research has shown that mixed-weight couples can experience prejudice and discrimination. In 2016, a study in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships asked people to rate couples who had similar or dissimilar BMIs. The dissimilar couples were rated less favorably. In a second study, survey takers were asked to pair individuals into couples. With no prompting, they instinctively paired men and women of similar sizes. When asked to give couples with mismatched BMIs relationship advice, they recommended they go on less public, less expensive dates and delay introductions to friends and family.15 Ouch.

It might be just as well that people prefer partners with similar bodies to theirs, as research has shown that mixed-weight couples can experience prejudice and discrimination. In 2016, a study in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships asked people to rate couples who had similar or dissimilar BMIs. The dissimilar couples were rated less favorably. In a second study, survey takers were asked to pair individuals into couples. With no prompting, they instinctively paired men and women of similar sizes. When asked to give couples with mismatched BMIs relationship advice, they recommended they go on less public, less expensive dates and delay introductions to friends and family.15 Ouch.

Weighing up the results

Given that we’re in the middle of an obesity epidemic, it’s perhaps unsurprising that such a large proportion of the people we surveyed wanted to lose weight. Or, given past gender gap studies16, that women’s body confidence was, on average, lower than men’s (even when they already looked like what men considered perfect).

But when each gender was given a private opportunity to say how they’d like their partners’ bodies to change, their desires didn’t match their partners’ own expectations for themselves. People overestimated how slim or well-built the opposite sex wished they were. These mismatched expectations presumably affect body confidence ratings, which were particularly low among women, regardless of age or relationship length. In fact, a woman with the body size and shape most men considered ideal had an average body confidence rating that was almost identical to a typical, somewhat overweight man.

One way for the sexes to better align their weight expectations is to talk more about how they feel about each other’s bodies. So, the next time your significant other asks “Do I look fat in this?” smile sweetly and say “One moment. I’m just going consult my 12-point body rating scale.”

But when each gender was given a private opportunity to say how they’d like their partners’ bodies to change, their desires didn’t match their partners’ own expectations for themselves. People overestimated how slim or well-built the opposite sex wished they were. These mismatched expectations presumably affect body confidence ratings, which were particularly low among women, regardless of age or relationship length. In fact, a woman with the body size and shape most men considered ideal had an average body confidence rating that was almost identical to a typical, somewhat overweight man.

One way for the sexes to better align their weight expectations is to talk more about how they feel about each other’s bodies. So, the next time your significant other asks “Do I look fat in this?” smile sweetly and say “One moment. I’m just going consult my 12-point body rating scale.”

Methodology

1,000 heterosexual American men and women in relationships ranging in age from 18 to 79, with a median age of 34, were presented with 12-figure body rating scales and asked to choose the appearance that most closely matched their own, their partner, what they wished they looked like, and what they wished their partner looked like. A 12-point muscularity scale was used by male respondents to select how well-built they currently are and wished they were. Women used the muscularity scale to indicate how muscular they wished their male partners were. Body genders also used a body shape scale to indicate which shape (“apple,” “pear,” “hourglass,” “inverted triangle,” etc.,) most closely matched their own and their current partner. For questions which required respondents’ current BMIs, their height and weights were used to calculate actual figures. For questions about what men and women wished they or their partners looked like, BMIs were inferred from body rating scale selections, which themselves were based on real people’s BMIs and appearances. This allowed the translation of body images to BMIs and weights and vice versa. Body weights that accompany the average body composites are based on average male and female heights of 5’9″ and 5’4″ respectively. When forming conclusions on the average body composites, it should be noted that this survey focused on body weights and shapes, which means respondents weren’t asked about other specific aspects of their own or their partners’ appearances, both actual and imagined. Factors like body hair, skin tone, hairstyles, etc., were therefore not considered.

References

- http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- https://nypost.com/2018/05/24/nearly-a-quarter-of-the-world-will-be-obese-by-2045/

- 4,590,279 instagram posts tagged with #bodygoal as of June 6th, 2018

- Stunkard A, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F (1983) Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness. Research Publications – Association for Research in Nervous & Mental Disease 60: 115–120.

- http://www.nspb.net/index.php/nspb/article/view/249

- http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.515.8089&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html

- http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3360454/Kim-Kardashian-reveals-17-lbs-weight-loss-wants-shed-53-pounds-birth-second-child.html

- http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/6514-australian-weight-loss-attitudes-and-products-june-2015-201510210006

- https://www.livescience.com/9834-hourglass-figures-affect-men-brains-drug.html

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/02/170214162852.htm

- Frederick, and Haselton, 2003; Furnham, and Radley, 1989; Hughes, and Gallup, 2003; Lavrakas, 1975.

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2643761?resultClick=3

- https://phys.org/news/2017-01-evidence-humans-partners-assortative.html

- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0265407516644067

- https://web.uvic.ca/~lalonde/manuscripts/2010-Body%20Image.pdf

Comments

Post a Comment